Yesterday, I learned my friend Jerry Adams died.

People die. It’s what we do. But I find his death hitting me particularly hard, even though I haven’t seen him in years.

I’ve known him since my first few months in New York City, over forty years ago. There was a time I saw him almost every day.

I’ve had a doozy of a 24 hours, and I spent most of yesterday thinking about Jerry and how fortunate I was to be young in New York City, circa 1980s.

Jerry and I were both able to live extraordinary lives during a time and place that seem almost magical now.

I miss those times. They were different than these.

On good days, I believe I can have a satisfying life no matter how old I get or how badly this world falls apart. I do not want to turn into one of these old people who grumble about life being better when we were young.

But I assure you—it was better. Sometimes I think I belonged to the last generation of people who knew how to have some fun.

No matter your political affiliation, “fun” is not the word that comes to mind when I think of modern life in America. And perhaps because it’s particularly awful now, the eighties seem particularly good.

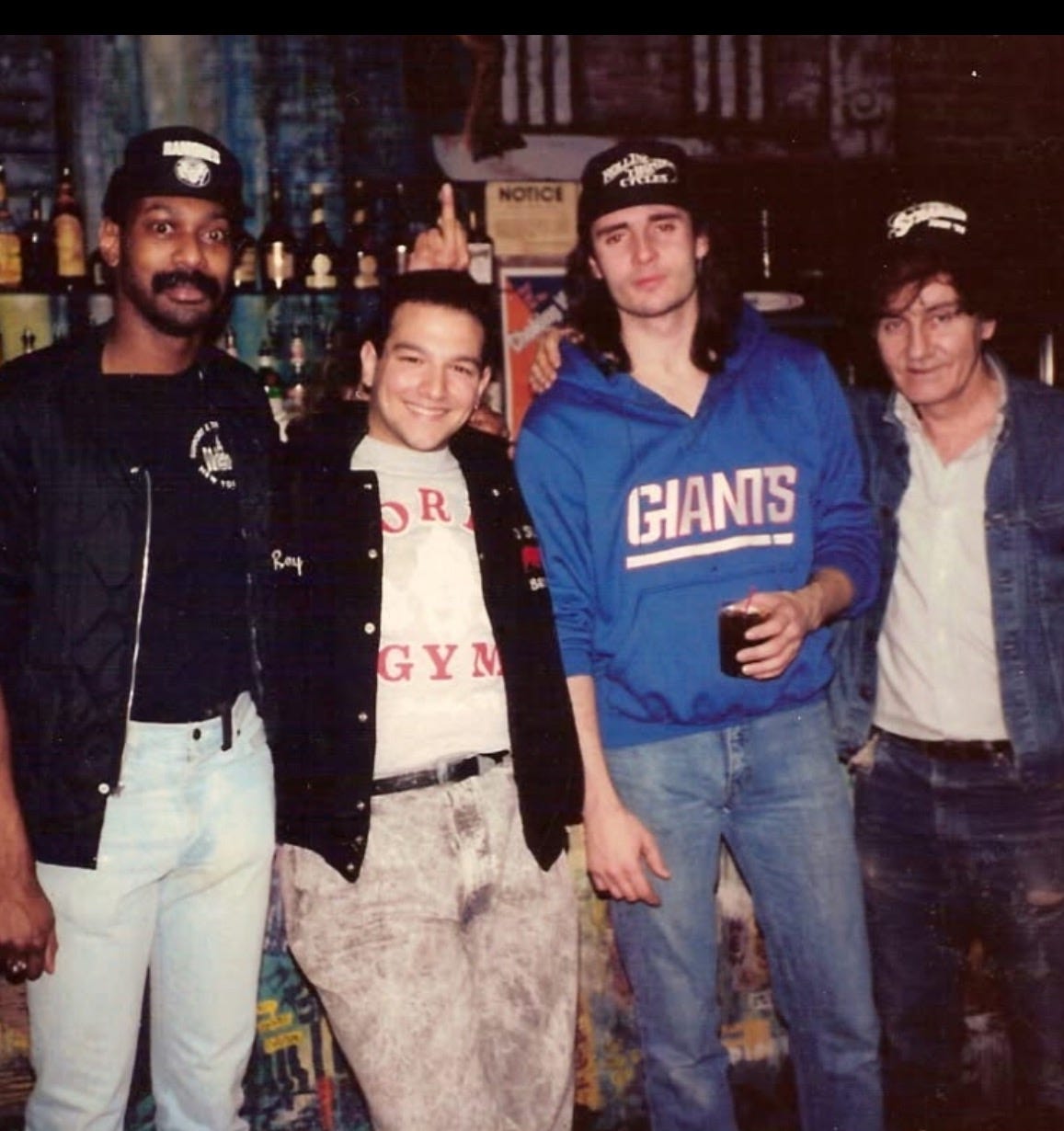

If you were part of the downtown New York City music scene then, it’s likely you knew Jerry.

He ran security at The Ritz. He knew almost everyone, and if anything was happening, he was there. He ran downtown like a cruise director, only a cool one.

He was kind, gentle, and funny as hell. Most of all, he had a rare and elusive intelligence about people. As a mutual friend remembered, he was a Black man who often had to wrangle tables of Hells Angels in the VIP room. He wore a bulletproof vest.

He was successful because of his preternatural ability with humans.

Years ago, I asked Jerry if I could write the story about how we met. It involved a musician I was hanging out with in my wilder days.

He wrote back,

“I love you, Liz, but I don’t know about telling that story.”

Out of respect for his wishes, I won’t tell the whole story. I’ll just give the punchline.

It is 1984, and I’m eighteen years old. I have just retired from the shortest modeling career in history. It’s about 9 am, and I’ve been out all night, stumbling out of some after-hours bar with a musician friend. I walk into my friend’s house and plop down on the living room couch.

The couch yelps. Then the couch curses and moves.

Unknowingly, I sat on Jerry. He’d been sleeping, and I didn’t notice he was there under a blanket. He took the blanket and stomped off to another room.

The next time I saw him I said,

“Didn’t I sit on you that time? Weren’t you on that couch?”

And we laughed and laughed, and were instantly friends.

Jerry worked at The Ritz, on 11th Street between 3rd and 4th Avenue. It eventually became Webster Hall. I worked at The Cat Club, on 13th Street, between 4th Avenue and Broadway.

I tended bar there for years, then I quit drinking. I suffered through nine months of pouring shots and slinging beers while abstaining myself. Our manager Don Hill had mercy and put me in coat check, where I could still earn tips but not go home reeking of booze.

I did coat check and worked in the box office, so I knew all the doormen. Jerry would come in almost every night after he worked, often with his friend Joey Ramone.

I cannot tell you how many Budweisers I opened for Joey Ramone.

One night in coat check, I saw Jerry come in with a particularly hot girl. She had her back to me, and Jerry was guiding her through the crowd. She was slim and had this gorgeous curtain of perfectly straight, beautiful red hair, and was dressed in head-to-toe black leather. I thought,

“Who is THAT?”

They turned, and Jerry waved.

The hot chick was Axel Rose.

A couple of days later, Jerry came in wearing a gorgeous leather Guns N’ Roses tour jacket. He came over to see me.

“Nice jacket,” I said.

“Thanks,” he replied. “Axel FedExed it to me.”

The eighties were a time when ordinary people could find themselves in extraordinary situations. That’s what downtown was like back then.

Before The Cat Club, I worked at Kenny’s Castaways and The Bitter End.

The bars closed at 4 am, so that’s when we partied, usually landing in an after-hours joint.

I distinctly remember getting lost in Central Park once (how I wound up there, I’ll never know) after dropping acid the first time. I returned to the East Village on the train, packed with Yuppies going to work on Wall Street, at around 8:30 am.

I pitied them. They thought making money was the ticket to happiness. We knew better.

One night, or early morning, the cook from Kenny’s noticed the time. He said,

“Oh no, my wife is going to kill me! We’re flying to Florida to visit her parents and I’m gonna miss the flight!”

He did not miss the flight.

He took a cab to the heliport and rented a helicopter to take him to the airport. The helicopter landed next to the People’s Express plane on the runway, and he bound up the steps to his waiting wife.

People’s Express was a budget airline. You could fly to Washington, D.C. for $29 from New York. I did more than once. You know what else I did?

I smoked cigarettes on the plane, because back then, grownups smoked.

When the cook was telling us the story, he said,

“Let me tell you what, I owned People’s Express. The flight attendants didn’t know who the hell I was.”

We were creative thinkers. We had to be.

To this day, my marker of civilization is an ashtray in a house, even though I no longer smoke.

You know what feels really good, as I write about the eighties?

Not apologizing for any of it. I enjoyed being awful.

It was long before 9/11, so there were no regulations at the airport. We didn’t have to take off our shoes, and you could fly without identification as long as it was a domestic flight.

I once flew to California on a ticket under the name (I have to make up the last name, the person is still living) Hugh Williams.

Hugh got sick at the last minute and couldn’t go to California with some mutual friends. They had his spare ticket, so I was invited.

Certainly, I’d like to go to California. Let me throw together a bag.

I remember the gate agent looking at the ticket, then looking at me.

“Your name is Hugh?”

“Yes,” I replied, staring right back at her. “I was named after my dad’s brother.”

She looked uncomfortable, because back then, it was bad manners to question a customer’s truthfulness.

“Do you have a driver’s license on you?”

“No, I don’t,” I said.

We stared at each other. Then I pulled out my trusty “how dare you” look, my entitled…what’s the word? We didn’t have a word for entitled white women back then. It was pre-Karen.

“My name is Hugh, and I’m not certain what the problem is here,” I said.

She let me on the plane.

I didn’t even have a credit card.

I flew back from London once into National Airport in January of 1987. It’s named Reagan Airport now, another sign of the end of civilization.

I had a passport, five British pounds and one personal check on me. When we got to the airport in D.C., it was shutting down due to a huge blizzard, rare for the area.

I cashed my five-pound-note at the exchange kiosk. I now had $12. Rumor had it that there were hotels giving rooms at half rate. I made my way with other panicked people to a cab. The cab driver promptly took my $12. Back then, they could double the price in bad weather.

Five of us arrived at a very fancy hotel. I checked into my room and wrote out the fee on my sole personal check.

I was beginning to come down with something. I had a sore throat, the result of a week of eating nothing but egg-mayonnaise sandwiches served at the Young Playwrights’ Festival.

I called my mother, who called the manager of the hotel. She told him if he let me order room service, she’d send him a check for the total. He agreed to do so.

I ordered a green salad and a fruit salad, delighted to have some fresh produce in my system. My mother’s word was good, and she sent the hotel payment for the meal.

Back then, you could be poor in New York.

We were all paid in cash, so although making the rent was hard, we had a fortune to spend at the end of every night.

And we got into trouble, and slept with other people’s boyfriends, wives, husbands, and roommates. I did too many drugs and drank too much. New York City was the wildest place on earth.

For a time, I loved it. Of course everything went south, and by everything, I mean me. But there are moments from those days I wouldn’t trade for anything.

One night I started to go into Kenny’s Castaways, and it was so packed, I could not get in the door.

Bobby Breiter was tending bar, and Eddie was at the door. Bobby proceeded to jump over the bar and pushed his way to me. He and Eddie then lifted me over the heads in the crowd, got me to the bar, and a man stood up and gave me his seat.

I had $5 to my name. I didn’t pay for a drink all night.

I told Secret Service about this, and how much I missed days like that. Which prompted him to say something which has become a go-to line whenever I’m bemoaning current circumstances:

“Not every day can be 1985.”

Jerry and I have a mutual friend, Raffaele. She was in a successful band, Cycle Sluts from Hell.

I always looked at Raff in awe. She was (and is, to this day) the most beautiful, coolest woman I’ll ever know. She is the eternal It Girl, and I’m a perpetual dork standing next to her.

As we’ve gotten older, we’ve become closer. I was never so cool as to tour with Motörhead in Europe, like she did. But she and I remember the same people, and some of the same days.

I called Raff when I read Jerry died. As I was speaking with her yesterday, I realized there are fewer and fewer people who remember these gorgeous, filthy, thrilling times.

Raffaele’s a writer as well, and a superb one. She’s the person to best read about this time.

People from “then” get more precious to me, even if we only run into each other once a decade now.

I’m alive in large part due to my friend Sharrie. She’s no longer living.

Life was not always good to her. But she loved music; it was what gave her strength, especially as a teenager in Kentucky. Her favorite band was Motörhead.

One day I saw that Motörhead was coming to The Ritz. I told Jerry I’d like to bring Sharrie, how much it would mean to her.

The night of the show, we arrived at the door, skipped the line, and were whisked upstairs to the VIP room. The tables followed the balcony, and went around in a horseshoe. We were given our own table and could look right down on the stage. Jerry stopped by to say hello and ask if everything was okay.

Sharrie wasn’t always treated as well as she deserved, but she was that night. Jerry gave that to her. I will never, ever forget her face at the show.

The magic Jerry created wasn’t just for his friends. He gave Sharrie, a girl he didn’t know, an experience to hear the band that got her through life.

Jerry did this instinctively. Like I said, he was wonderful with humans.

Every day can’t be 1985. But I knew a lovely man named Jerry Adams.

Loved your story .

1985 began my wild days at 30 years old filled with suppressed rage .

My anger was thankfully channeled for a brief time before it raged again .

The AIDS epidemic healed me in many ways . I had the humbling opportunity to care for young men at the time . We didn’t know it was what it was . Our diagnosis at the time was FUO ! (Fever Unknown Origin ). As much as I cared for them there was no saving their life at that time but little did they know they were saving mine .

I feel the same way about 1975.