When I was fifteen years old, my father died.

He and I were so close, so alike, my mother Bettie referred to us as “the twins.”

When she and I had problems, she’d suggest that daughters and fathers get along better, as did mothers and sons.

This rather left me in the soup when he died. I was alone in the world. I can’t say it was the truth, but it is how I felt.

I saw his older sister, my Aunt Sally, about a month after his death. I walked into the living room, our eyes locked, and my breath left me.

She had my father’s eyes. It was summertime, and her arms were bare. They were the same shape as his. Her skin was his skin.

In Sally, my father was in the room. I was able to see a part of him, alive and well.

After their visit, she and I started writing each other.

Sally and I have kept a correspondence going for 44 years. It started with letters, then email, then texts. I have over a dozen floppy discs of our emails in a safe deposit box in addition to all of her letters.

My father had a son from his first marriage. My older brother was estranged from us for forty years through no fault of his own. We reunited in 2011. He and I have visited Sally together in Texas every year since, barring the pandemic.

It is always the highlight of my year.

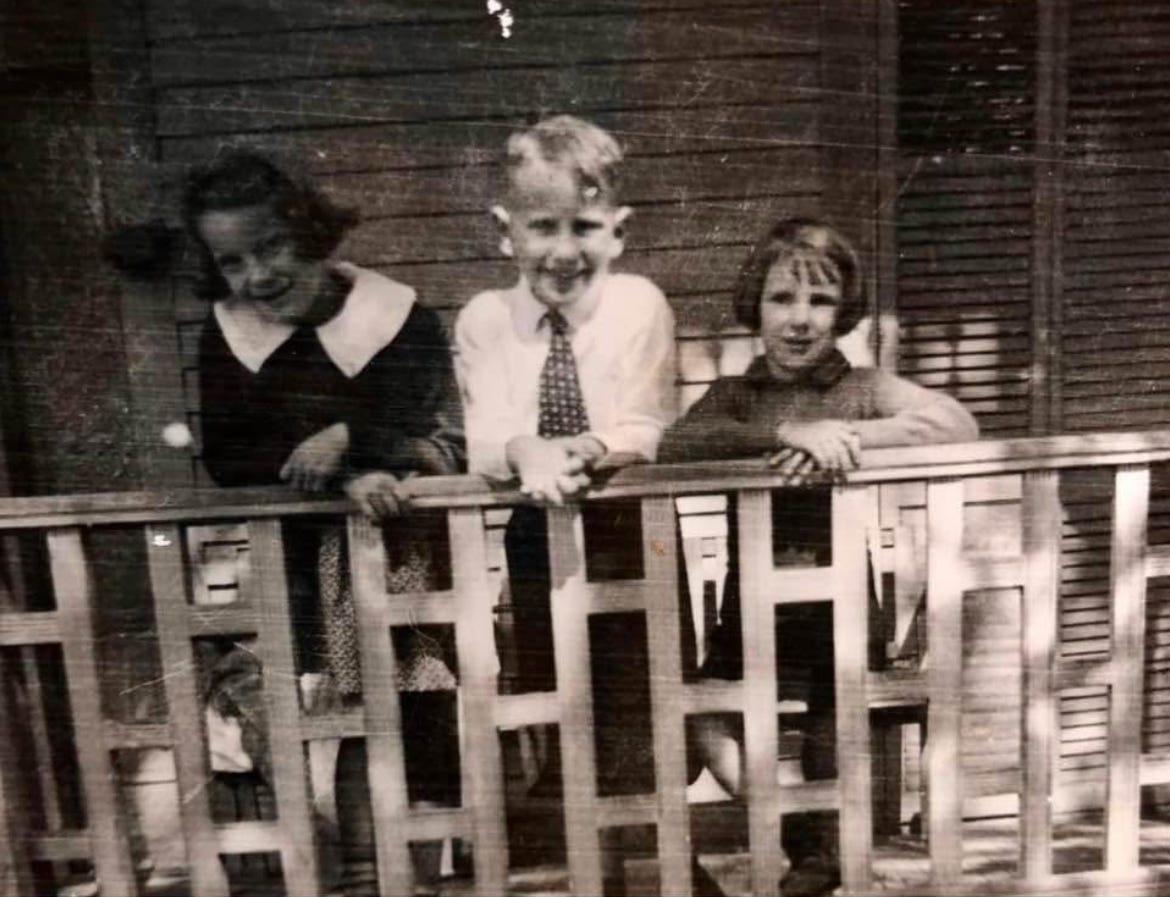

Sally and her husband Garland had six kids. All four of her daughters live in the same small town as she, where my dad David, Sally, and their younger sister Bittie grew up. Sometimes when my brother and I arrive, everyone descends on her house.

I only saw these cousins twice as a child.

Once, they all arrived in Virginia for a visit. I was four years old. Sally loved to talk about that visit, and how my mother cooked a ham and saw that everyone had beds.

My cousin Amy, a year older than I, had the single of Donny Osmond’s “Puppy Love.” We played it so often my mother referred to it as “Oh, that song!” for the rest of her life.

On February 18th, Sally died at the age of 94 at her home in Texas. She was the same age as my mother on the occasion of her death last year.

My dad and his two sisters were raised by their maternal grandparents and their Aunt Idy after they were orphaned as children. Their grandfather was a doctor. Their late mother Marjorie had a brother, my great-uncle, who was the muralist Kindred McLeary.

Sally has the most interesting children and grandchildren. Art and medicine have continued through the generations of her family.

Sally was a fine artist and worked in several mediums. Sally’s descendants include artists, naturalists, adventurers, travelers, animal rescuers, readers; a nurse, doctor, nutritionist, physical therapist, chef, at least one polyglot, a Tai Chi devotee, and one Ironman grandson who had his pocket picked in Italy. He pursued the thief so quickly he got his wallet back.

She and I were laughing about that story less than a month ago.

That’s just some of them. They’re an interesting bunch.

The entire lot seem comfortable in their own skin. She raised a whole family who are at ease with themselves.

This seems a miracle, especially to someone like me. I haven’t been comfortable with myself since 1972.

Sally was interested in people and had an insatiable curiosity. I have a feeling she got a kick out of seeing who her kids became.

I know I shouldn’t compare how I feel about Sally’s death to how I felt after my mother’s, but I can’t help it.

My oldest cousin Thea asked me a few days ago what was the hardest thing after Bettie died. I thought for a couple of minutes, and answered,

“The hardest things were before she died. Not after.”

I held my mother as she took her last breath. I’d been taking care of her for years, commuting between Virginia and New York.

When she died, I accomplished something I wasn’t certain I could. I’d always planned on taking care of her when she was old. I wanted to be with her when she died.

There were many times I thought it might not be possible. She was difficult. I’d stopped looking to her for maternal comfort years ago.

I loved her. And when she died, I was relieved.

Thea called me soon after Sally died. I knew as soon as I saw her number what had happened; but when she told me, I burst into tears. I cried several times a day for four days.

The loss of Sally is unlike any loss I’ve experienced in my adult life. As I said to Thea,

“I feel the way I imagine people feel when they lose a parent. I wasn’t this sad after Bettie’s death. I feel a little guilty.”

“And Sally would love that,” Thea said.

Well, that made me laugh. Sally would indeed love it. Who wouldn’t love being that important to someone?

I’d been keenly tuned into Sally’s decline over the past couple of months.

I can’t explain it, just like I can’t explain waking up the moment my father died in 1981. I was in New York, three hundred miles away. I woke up and felt him. I knew he was gone.

I’ve been having similar experiences with Sally. My older brother and I visited her earlier than usual this year, after one of her daughters suggested we might come sooner rather than later.

Sally didn’t want my cousins to tell anyone she’d entered hospice. I understand it completely. When people know you’re dying, they treat you differently.

When I walked into her kitchen at the end of last month, I kept my voice causal when I went over and asked how she was doing.

She was at her table in her wheelchair. I had to ask loudly, as she was almost completely deaf. She answered just as loudly,

“I don’t feel close to death!”

I laughed, and told her she didn’t look close to death, either. It was the truth. She looked fantastic.

We left Texas on January 30th. On Sunday the 16th, I woke up and felt Sally hovering overhead, briefly visiting. I called Thea later.

“Elizabeth, you’re good at this,” Thea said.

Sally had changed that day. She’d stopped eating, and started talking to people who weren’t visible to others. But Thea also reported Sally was laughing a lot. She was happy.

Imagine going out of this world laughing. How’s that for a life well lived?

A couple of days ago, I told my younger brother about my experience with Sally’s death, and how I’d felt her leaving in stages.

To my surprise, he was interested. He is the least New-Agey person I know, and his faith is firmly rooted in science.

But he’d been reading a book about quantum particles. He was curious if quantum particles had something to do with what I noticed as Sally made her exit.

I don’t know a lot about quantum mechanics. But I’ve always thought my sensitivity to death was a practical matter that science would eventually explain.

Energy cannot be destroyed, and I’ve long suspected humans constantly emit electrical signals.

As receptors to this energy, some people are like wood, and don’t feel the electric impulses much. They thud right off them.

I, on the other hand, am more like copper. This really helps my poker game.

I’ve given up fighting The Universe, if I can help it. I don’t have to understand everything.

Sally was a voracious reader. I’m convinced my love of books was inherited from this side of my gene pool. No matter where she went or what she was doing, she was reading.

She was a highly talented artist who worked in several mediums. When my younger brother and I were splitting up my mother’s art collection, one of my first picks was a painting of hers called “Doors.” She’d given it to Bettie.

Sally adored my mother and thought of her as a sister. My mother felt the same way.

Sally never forgot that when my father got a malignant melanoma, my mother moved him back into our house and cared for him until his death, even though they were long divorced. She buried him in our family cemetery, and is buried next to him now.

Sally and her younger sister Bittie were very close. They would go on birding trips together, rode bicycles, and did familial genealogical excursions to other states, tracing down our ancestors. They wrote each other constantly.

In August of 1999, I opened a letter from Sally. I was living in Manhattan.

Sally wrote that a few months before, Bittie was walking into her living room and her femur broke. In the hospital, it was discovered she had lung cancer, which had metastasized to her bones. That’s what caused the break.

Sally was in Texas. She went to Florida immediately and stayed to care for Bittie at the home she shared with her daughter Jenny, an only child and cousin I’d never met.

I’d seen Bittie that year in Northern Florida, when she drove up to meet me at White Oak, where I was vacationing with my family. I remembered that Bittie had complained about neck pain.

Bittie was not a complainer. That pain was cancer.

In Sally’s letter, she wrote Bittie did not want people to know she was sick. But Sally was now writing because Bittie was actively dying.

I called her and said I’d like to come if it were alright with Jenny. In an act of extraordinary generosity, Jenny invited me to come be with them. I was on a plane that night.

I spent three days with Sally watching Bittie die. This is the time I learned how hard the body works to stay alive. Bittie opened her eyes when I first arrived. For the next 72 hours I thought every breath might be her last.

Sally suffered too much loss in her life. Her mother died at six, her father at eleven. Kindred McLeary died at the age of 44. My oldest cousin Scott, Sally’s first child, died when he was 21 years old in a car accident. My father died when he was 49. Uncle Garland died over a decade ago.

But losing Bittie, at 66, was life altering for Sally.

Her son Scott was in the Navy, and visited us once on leave. I was five.

He got to our house in the early morning, and waited on the porch swing until he heard sounds that we were up.

I immediately fell in love with him. He was a sailor in uniform complete with jaunty white hat, and he would pick me up in his arms. I remember being at the train station when he left, and how he doubled back to kiss me goodbye. He remains to me the most romantic figure on earth.

Even after his death, Sally didn’t lose her love and curiosity of life.

I found it incredible Sally had six children. I reveal my deep prejudice when I admit I tend to think of women with a lot of children as different from women who love books, quiet, and art.

I could never figure out how to resolve these seeming contradictions in her, so a few years ago, I finally asked her.

“My mother died when I was five,” Sally said. “So having a family was always important to me. Family is important.”

When I told Secret Service she died, he said,

“What an interesting legacy she left to the world.”

That’s the truth. She is also responsible for a literary character.

It was Sally who named my husband Secret Service, after seeing a photo of him in a gondola in Venice with his sunglasses on.

“He looks very Secret Service!” she wrote.

“He’s protecting me from gondoliers,” I replied.

Secret Service muttered,

“More like protecting gondoliers from you.”

Oh, Elizabeth, I would have loved to have met your Aunt Sally. What a remarkable woman. I'm so sorry for your loss.

Beautiful tribute to Aunt Sally and your family !