An argument develops in my mind.

I can’t get this right, I tell him. How do I choose what to put in? Impossible.

That’s no excuse, Fred replies.

When Tommy called late Friday night, I couldn’t answer the phone.

I tried. But I couldn’t get the headset working, or the volume right, and I couldn’t hear him. Tommy hung up before we spoke. I tried to figure out how to call him back, but it’s safe to say my brain wasn’t working properly. I know how to use a phone.

I think I needed a minute to try and…what. Accept it? Realize it? Fred’s death was both expected and impossible.

Tommy then called on the land line, so the name that appeared on my phone was,

When I answered it was like we were fifteen years old again. We reverted to the age we were when Fred taught us.

I said hi. He said hi. Awkward teenagers on the telephone. Tommy finally said,

“I think you know why I’m calling so late.”

“Yes,” I replied. “I think I do.”

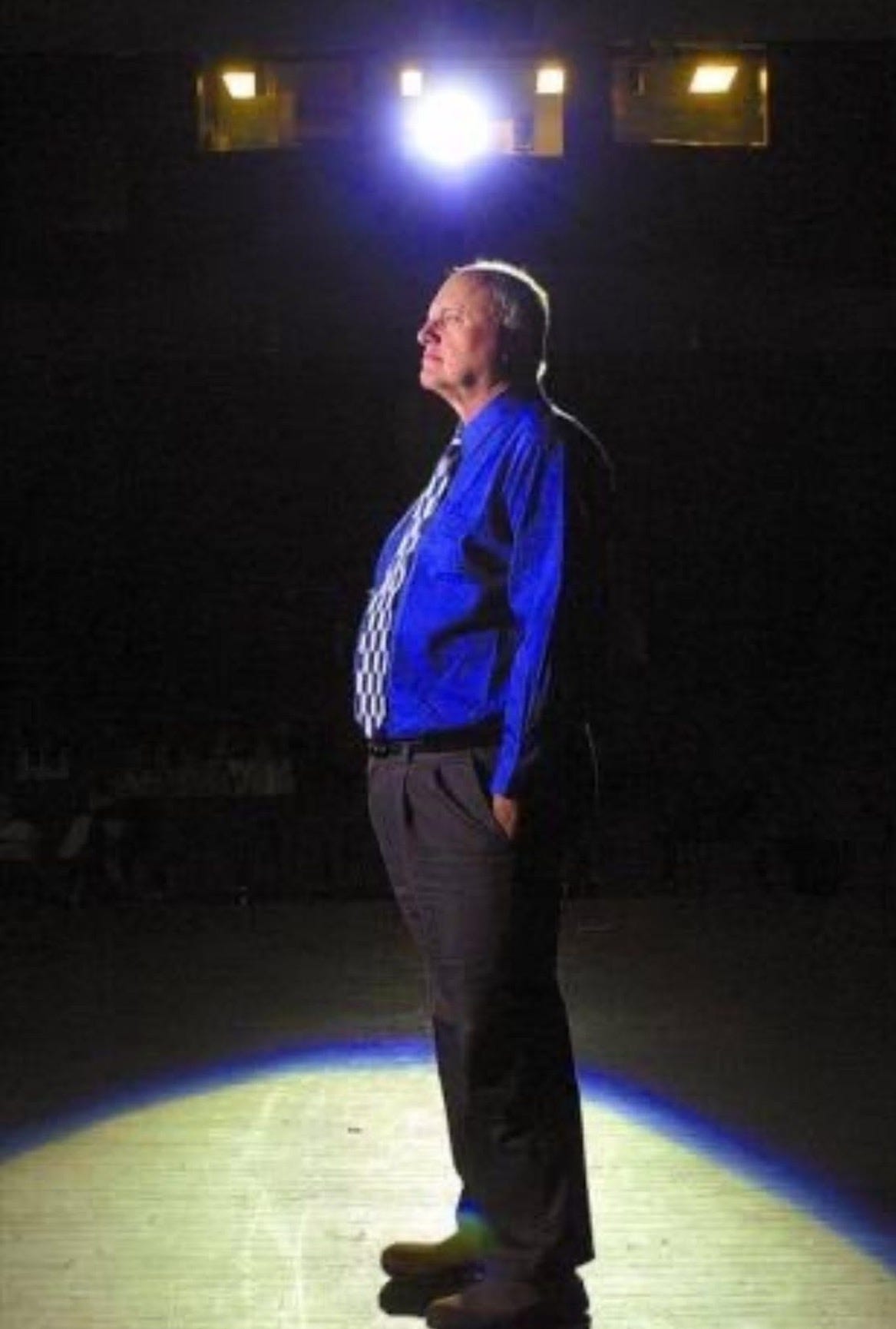

Fred was the Southern Zeus.

To understand my origin story, how I was born of him, consider the time and place—Virginia in the 1970s. As Fred would say,

Deadly dull.

I do not have many friends. I spend my life in books. Reading is my vocation.

I have recently survived the worst year of my life, when I was separated from my best friend Tammy in sixth grade. She was in the classroom next door, and I was left with the cast of Lord of the Flies. I was constantly picked on, and the teacher, with her blue eyeshadow and polyester twin sets, was in on it.

To say I hated school was an understatement.

It is September 13th, 1978.

I have just turned thirteen years old. I go into town to bring Miss Edmo Lee a bouquet of fall crocus from our house, which was her childhood home. It’s her hundredth birthday.

My great-Aunt Nancy is there with me, chatting with Miss Edmo. I immediately become bored. I turn my head to the left.

Walking down Prince Edward Street is Fred Franklin. He is wearing clogs.

My mouth drops open. Never in the history of Fredericksburg has a grown man had the audacity, the nerve, to put on a pair of clogs and walk outside.

I know who he is immediately. I’d heard of him.

The drama teacher. I’d spotted the actual clog-wearing unicorn in the wild.

He smiles at our little group of old ladies and lost children, curtly nods his head, and walks on.

I must know this man. In his presence, life could begin.

The following year I started high school.

There was a big mess. We had only one high school, and suddenly, there were twice as many students.

The school board got caught with their pants down. Construction was started on a new school, but it wouldn’t be finished for two years.

What to do in the meantime? Split shifts.

Students who lived in the southern part of the county, like Tammy and me, started our high school days while it was still dark outside; we were dismissed at 11:15 am. The rest of the county kids came to school in the afternoon.

Fred Franklin spent his last two years as an English teacher with us in the morning, before he went to the new high school to head its drama department.

I don’t remember much from those two years. I was not a morning person. But I remember class with Fred.

We never knew what he’d do or say. He had a notoriously acerbic wit—good luck to you if you tried to cross him. He could handle any unruly student with one raised eyebrow and a sharp word.

We read Shakespeare aloud. He made us write sonnets.

Fred was required to teach the same curriculum as other teachers, but he handled the mundane differently. One morning he came in and said,

“Look. I have to make sure you know something. Does everyone know what this is?”

I can’t remember what “this” was. Something he was required to teach.

He looked at our nodding heads.

“If I were to give you a test tomorrow, you’d be able to answer correctly? Yes? Good,” he said, “That’s done.”

Then he moved on, and made us write a one-act play.

There are certain phrases that are classic Fred. Please imagine them said in a Tidewater accent. He was born and raised in Virginia’s Northern Neck.

One thing a day, baby. I do one thing a day, fold my hands, and then I’m done. This happens to be an excellent formula for keeping one’s sanity.

You can’t get shit. Self-explanatory, and correct.

Thank you Jesus. This is said two different ways. The first is with equal emphasis on all three words, almost as an aside:

We finally got home, thankyoujesus.

The second is with emphasis on the word Jesus. When Jesus got emphasized, it meant an event was particularly trying.

And then, FINALLY, we got home. Thank you JESUS.

The phrase I most associate with him is,

It’s the end of the world.

A true wit makes you fall in love with the English language.

We fell in love with storytelling because he loved a good story, and there was no better feeling on earth than listening to Fred Franklin tell one.

He was different than other teachers. He was human. He could barely put on clean clothes. He was always wrinkled, always needed a haircut, usually overweight. He never remembered to put oil in the car or do practical things. His work took precedent.

He didn’t lie to us.

He was stuck in this small town in Virginia with us. He wanted more, just like we did.

He delivered, in literature and drama.

A child in high school today could never have the kind of relationship I had with Fred. When I was a teenager, I’d just show up at his door and knock. He’d open it and say,

“Oh, hello.” Then turn and walk to the sun porch where he had his chair. I’d sit across from him and we’d talk.

We went out to eat. One day I called him and told him my grandmother gave me $100. We went to the fancy Italian restaurant and then out to the Sheraton, where they had dancing.

He was a marvelous dancer. He picked me up and twirled me around in the air. An elderly couple came up to us and said,

“You two are the best dancers in the room!”

One of the primary relationships of my life would not have occurred had I met him today. Society wouldn’t allow it.

When I left Virginia for New York and returned to visit, the first order of business was going over to Fred’s house. I’d report in on my life.

I was not alone. For many of us, Fred was home. We’d show up at his house unannounced and talk, whether returning from adventures, or the deadly tedium of our elderly parents, or travelling to London, or falling in love, or some other epic disaster in which we found ourselves.

Because he made storytellers of us, we returned to him and told him ours.

Another close student to him was Jackie. She and I were talking on the phone last week, after Fred had been given last rights. We reverted to our teenage years as well, and talked for an hour and a half.

“I cannot imagine,” I said, “what my life would have been like had I not had Fred.”

“A completely different life,” Jackie said.

Yes.

Fred taught us forty-five years ago. In the last months of his life we surrounded him.

Tommy was his main caregiver who lived close by and managed everything for him. Tommy took care of him with a love and attention to detail for which I will always be grateful.

He wasn’t just Fred’s student; he’d gone to school and become a drama teacher like Fred, teaching in the same county.

Fred’s students visited him: Crunchy, Mary, Jennifer, the other Tom, Tammy, Mark, Jackie, and countless others.

This spring, I started to stay at Fred’s house when I’d go down. He liked having me there.

When I was fifteen and knew nothing, I briefly imagined I’d marry Fred. He and I would live together and the entirety of our lives would be spent reading books and talking about them.

These last two visits gave me a whiff of how I imagined our life together. I was glad to have those days.

In April, the day after Jennifer’s theatre company did a performance in his Shakespeare Garden, the local paper came and a reporter interviewed him. The story was on the front page the next day. I read the story aloud to him.

As I was sitting there reading, an older man came in the front door.

He introduced himself, saying,

“Mr. Franklin, I just had to come and shake your hand. You taught me in 1965 at Gayle Jr. High, when I was twelve years old.”

I was born in 1965.

Our lifelong loyalty to him was the most natural thing in the world.

When I was with him last week, I told his wonderful aide Speedy a story while she made Fred’s bed.

I moved back to Virginia for a few years once and married a man there who worked as a mechanic. One day, Fred locked his keys in his car.

“Elizabeth,” he said. “Do you think Darrell can get the key out of my car?”

Fred said on more than one occasion that he loved Darrell more than I did. Fred was full of love for anyone who could fix what was broken in his world, who could do something practical.

Darrell adored Fred, and happily went down to retrieve his keys.

I got another call a day or two later.

“Elizabeth,” Fred said.

Fred had certain qualities to his voice. I heard it loud and clear. This particular quality was,

I have stepped into shit this time. It’s the end of the world.

Then he said, in a whisper,

“I did it again. I locked the keys in again.” Fred said again so it rhymed with a rain, with the emphasis on the last syllable.

“You didn’t,” I said.

“I did,” he confessed.

I called Darrell. This time he sighed, got his Slim Jim, then gave a little chuckle, muttering,

“Fred.”

He went and unlocked his car. A-gain.

You know what happened next. Nobody locks their keys in the car three times in a week, unless they’re Fred Franklin. He could do two things: teach school and direct plays. The rest of life just kind of got away from him.

“Darrell unlocked the car again,” I told Speedy, “but he wouldn’t look at Fred or speak to him.”

It was the last time I heard Fred laugh.

Virtue bored Fred. He loved a good revenge story, particularly when he was the one crafting it.

After I’d graduated school and was working in New York as a model, he called me up one day while I was in town.

“Put on something,” he said, “I’m taking you to Washington.”

He was asking me to dress up, which was odd. He could usually care less about clothes.

I put on an outfit and drove over. Fred looked downright dapper, in a tie and suit jacket.

“Where are we going?” I asked him in the car.

“We’re just going up the road for a minute,” he said. “I have to do this one thing first.”

“What?” I asked. He didn’t answer.

Eventually he pulled into the parking lot of a high school. There were a lot of cars there. The Senior Dinner Dance was happening.

He took me inside. At one of the tables sat a bunch of teachers, and what looked like one or two school officials.

Fred took me over to their table.

He introduced me first to one of the men, who got up to greet me. Fred said,

“We’re just going to Washington for the evening and thought we’d stop by to say hello.”

It began to dawn on me that I was there to punish the man at the table. I knew my part.

I began to flutter my eyelashes at Fred and look at him adoringly. I took his arm. We finally waved goodbye to the sputtering school official. I leaned into Fred’s ear to whisper something as we walked out.

As we went out the door to the car, Fred said,

“Good. That’s done.”

Then we got in and drove back to his house.

In the quiet of the past few days, in the stillness following my initial grief, something true occurs to me.

Fred was the love of my life.

And not just mine, but of fellow teachers, choreographers, actors, directors, set designers, lawyers, software creators, cleaners, sculptors, librarians, painters, insurance salesmen, real-estate magnates, surfers, florists, and mechanics.

And as I write about him, I think death is ridiculous. Fred lives in every word I’ll ever write.

This essay officially kicked off the healing process for me, Elizabeth. I'm sure it will for many others. Thank you for that. The grief has just turned down a small notch.

Such a beautiful story! He sounds like a wonderful mentor and friend! I'm so sorry for your loss. The director of the Child Care center I taught at for 20 years, died last year, and I was/am still devastated by her loss. She was an amazing, caring, and spiritual woman.